Communicating Between Microservices

This article is featured in the new DZone Guide to Microservices. Get your free copy for more insightful articles, industry statistics, and more!

One of the most important aspects of developing microservices rather than a monolithic application is an inter-service communication. With a monolithic application, running on single process invokes between components are realized on language-level method calls. If you are following the MVC design pattern during development, you usually have model classes that map relational databases to an object model. Then, you create components which expose methods that help to perform standard operations on database tables like create, read, update, and delete. The components most commonly known as DAO or repository objects should not be directly called from a controller, but through an additional layer of components which can also add some portion of business logic if needed.

Usually, when I’m talking with others about migrating from a monolith to a microservices-based application, they see the biggest challenge just in changing their communication mechanism. If you’ve ever looked back on working on a typical monolithic application with a database backend, you probably realized how important it was to properly design relations between tables and then map them into object models. In microservices-based architecture, it’s important to divide this often very complex structure into independently developed and deployed services, which are also forming a mesh with many communication links. Often the division is not as obvious as it would seem, and not every component which encapsulates logic related to a table becomes a separated microservice.

Decisions related to such a division require knowledge about the business aspects of a system, but communication standards can be easily defined, and they are unchangeable no matter which approach to architecture we decide to implement. If we are talking about communication styles, itis possible to classify them in two axes. The first step is to define whether a protocol is synchronous or asynchronous.

Synchronous – For web application communication, the HTTP protocol has been the standard for many years, and that is no different for microservices. It is a synchronous, stateless protocol, which does have its drawbacks. However, they do not have a negative impact on its popularity. In synchronous communication, the client sends a request and waits for a response from the service. Interestingly, using that protocol, the client can communicate asynchronously with a server, which means that a thread is not blocked, and the response will reach a callback eventually. An example of such a library, which provides the most common pattern for synchronous REST communication,is Spring Cloud Netflix. For asynchronous callback, there are frameworks like Vert.x or Node.js platform.

Asynchronous - The key point here is that the client should not have blocked a thread while waiting for a response. In most cases, such communication is realized with messaging brokers. The message producer usually does not wait for a response. It just waits for acknowledgment that the message has been received by the broker. The most popular protocol for this type of communication is AMQP (Advanced Message QueuingProtocol), which is supported by many operating systems and cloud providers. An asynchronous messaging system may be implemented in a one-to-one(queue) or one-to-many (topic) mode. The most popular message brokers are RabbitMQ and Apache Kafka. An interesting framework which provides mechanisms for building message-driven microservices based on those brokers is Spring Cloud Stream.

Most think that building microservices is based on the same principle as REST with a JSON web service. Of course, this is the most common method, but as you can see it is not the only one. Not only that, in some articles, you might read that synchronous communication is an anti-pattern, especially when there are many services in a calling route.

The other frequent comparison we might read about compares microservices to SOA architecture. In SOA, the most common communication protocol is SOAP. There has been a great deal of discussion as to whether SOAP is better than REST or vice versa. As we all know, they each have advantages and drawbacks, but REST is lightweight and independent from the type of language, so it has won the competition for modern applications, and is slowly taking over the enterprise sector. Honestly, I don’t have anything against microservices based on SOAP if there is a good reason for it.

Let’s look back at the criteria of division to different types of communication. I have already mentioned that we can classify them into synchronous vs. asynchronous, the latter of which defines whether the communication has a single receiver or multiple receivers. In one-to-one communication, each client request is processed by exactly one service instance, while each request can be processed by many different services. It is worth it to point out here that one message is received by different services, but usually it should not be received by different instances of a single service. Microservices frameworks usually implement a consumer grouping mechanism whereby different instances of a single application have been placed in a competing consumer relationship in which only one instance is expected to handle an incoming message.

For one-to-one synchronous services, the same can be achieved with a load-balancing mechanism performed on the client side. Each service has information about the location addresses of all instances that are calling services.This information can be taken from a service discovery server or may be provided manually in configuration properties. Each service has a built-in routing client that can choose one instance of a target service, using the right algorithm, and send a request there. These are the most popular load balancing methods:

Round Robin - The simplest and most common way. Requests are distributed across all the instances sequentially.

Least Connections - A request goes to the instance that is processing the least number of active connections at the current time.

Weighted Round Robin - This algorithm assigns a weight to each instance in the pool, and new connections are forwarded in proportion to the assigned weight.

IP Hash – This method generates a unique hash key from the source IP address and determines which instance receives the request.

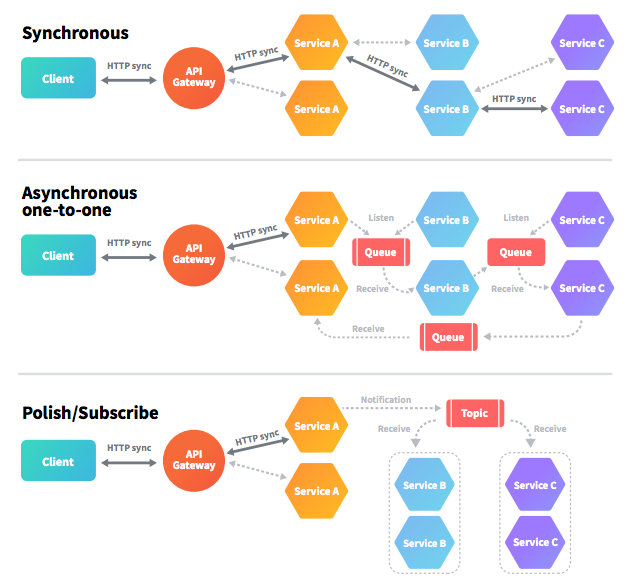

Here’s a figure that illustrates different types of communication used for microservices-based architecture, assuming the existence of multiple instances of each service:

In more complex architectures, there can be cases where those three communication types are mixed with each other. Then, some microservices are built on the basis of synchronous interaction, some on one-to-one messaging, and others on a publish/subscribe model.

In more complex architectures, there can be cases where those three communication types are mixed with each other. Then, some microservices are built on the basis of synchronous interaction, some on one-to-one messaging, and others on a publish/subscribe model.

There’s been a lot of talk recently about reactive microservices, so I think it is worth it to devote a few words to it. It is based on the Reactive Programming paradigm, oriented around data flows and the propagation of change.Such microservices are non-blocking, asynchronous, event-driven, and require a small number of threads to scale.Their greatest advantage is excellent performance with little resource consumption. The most popular frameworks for building reactive microservices are Lagom and Vert.x.

Let’s get back to synchronous request/response communication. It is very important to prepare systems in case of partial failure, especially for a microservices-based architecture, where there are many applications running in separated processes. A single request from the client point of view might be forwarded through many different services. It’s possible that one of those services is down because of a failure, maintenance, or just might be overloaded, which causes an extremely slow response to client requests coming into the system. There are several best practices for dealing with failures and errors.The first recommends that we should always set network connect and read timeouts to avoid waiting too long for the response. The second approach is about limiting the number of accepted requests if a service fails or responses take too long. In this case, there is no sense in sending additional requests by the client.

The last two patterns are closely connected to each other. I’m thinking about the circuit breaker pattern and fallback. The major assumption of this approach relies on monitoring successful and failed requests. If too many requests fail or services take too long to respond, the configured circuit breaker is tripped and all further requests are rejected. On the other hand, fallback provides some portion of logic which has to be performed if a request fails or circuit breaker had been tripped. In some cases, it could be useful, especially when data returned by a service is not critical for the client or does not change frequently and may be taken from the cache. The most popular implementation of the described patterns is available in Netflix Hystrix, which is used by many Java frameworks, providing components for microservices like Spring Cloud or Apache Camel.

Implementation of a circuit breaker with Spring Cloud Netflix is quite simple. In the main class, it can be enabled with one annotation:

@SpringBootApplication

@EnableFeignClients

@EnableCircuitBreaker

public class Application {

public static void main(String[] args) {

SpringApplication.run(Application.class, args);

}

}To communicate with another microservice, we can use the Feign REST client, which handles fallback. Here, we return an empty list:

@FeignClient(value = “account - service”, fallback =

AccountFallback.class)

public interface AccountClient {

@RequestMapping(method = RequestMethod.GET, value = “/accounts/customer / {

customerId

}”)

List < Account > getAccounts(@PathVariable(“customerId”) Integer customerId);

}

@Component

public class AccountFallback implements AccountClient {

@Override

public List < Account > getAccounts(Integer customerId) {

List < Account > acc = new ArrayList < Account > ();

return acc;

}

}Hystrix default settings may be overridden with configuration properties. The property visible below sets the time after which the caller will receive a timeout while waiting for a response:

hystrix.command.default.execution.isolation.thread.

timeoutInMilliseconds=500This article is featured in the new DZone Guide to Microservices. Get your free copy for more insightful articles, industry statistics, and more!