Data Consistency in Microservices Architecture

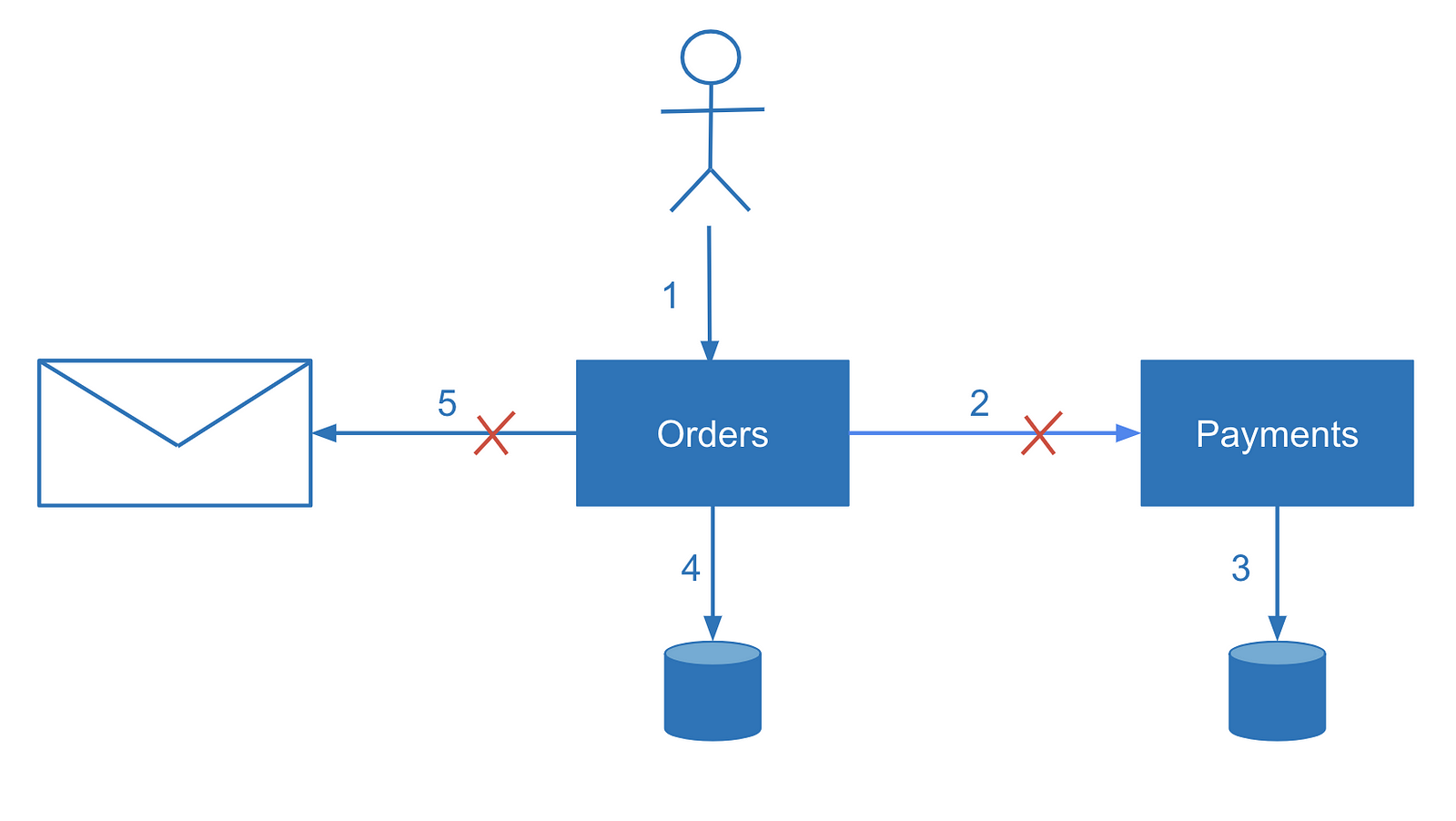

In microservices, one logically atomic operation can frequently span multiple microservices. Even a monolithic system might use multiple databases or messaging solutions. With several independent data storage solutions, we risk inconsistent data if one of the distributed process participants fails — such as charging a customer without placing the order or not notifying the customer that the order succeeded.

In this article, I’d like to share some of the techniques I’ve learned for making data between microservices eventually consistent.

Why is it so challenging to achieve this? As long as we have multiple places where the data is stored (which are not in a single database), consistency is not solved automatically and engineers need to take care of consistency while designing the system. For now, in my opinion, the industry doesn’t yet have a widely known solution for updating data atomically in multiple different data sources — and we probably shouldn’t wait for one to be available soon.

One attempt to solve this problem in an automated and hassle-free manner is the XA protocol implementing the two-phase commit (2PC) pattern. But in modern high-scale applications (especially in a cloud environment), 2PC doesn’t seem to perform so well. To eliminate the disadvantages of 2PC, we have to trade ACID for BASE and cover consistency concerns ourselves in different ways depending on the requirements.

Saga Pattern

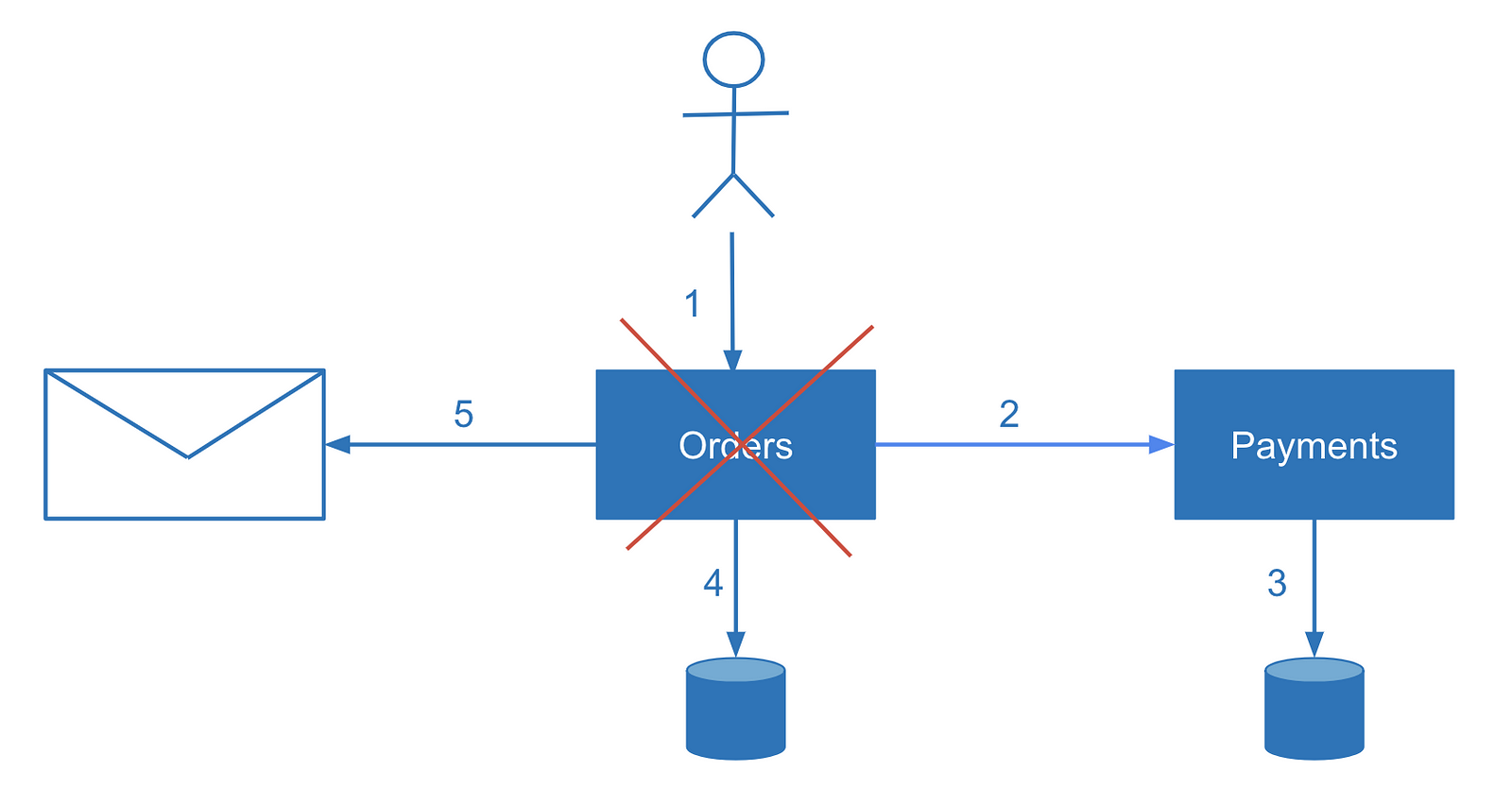

The most well-known way of handling consistency concerns in multiple microservices is the Saga Pattern. You may treat Sagas as application-level distributed coordination of multiple transactions. Depending on the use-case and requirements, you optimize your own Saga implementation. In contrast, the XA protocol tries to cover all the scenarios. The Saga Pattern is also not new. It was known and used in ESB and SOA architectures in the past. Finally, it successfully transitioned to the microservices world. Each atomic business operation that spans multiple services might consist of multiple transactions on a technical level. The key idea of the Saga Pattern is to be able to roll back one of the individual transactions. As we know, rollback is not possible for already committed individual transactions out of the box. But this is achieved by invoking a compensation action — by introducing a “Cancel” operation.

Compensating operations:

In addition to cancelation, you should consider making your service idempotent, so you can retry or restart certain operations in case of failures. Failures should be monitored and reaction to failures should be proactive.

Reconciliation

What if in the middle of the process the system responsible for calling a compensation action crashes or restarts. In this case, the user may receive an error message and the compensation logic should be triggered or — when processing asynchronous user requests, the execution logic should be resumed.

To find crashed transactions and resume operation or apply compensation, we need to reconcile data from multiple services. Reconciliation is a technique familiar to engineers who have worked in the financial domain. Did you ever wonder how banks make sure your money transfer didn’t get lost or how money transfer happens between two different banks in general? The quick answer is reconciliation.

In accounting, reconciliation is the process of ensuring that two sets of records (usually the balances of two accounts) are in agreement. Reconciliation is used to ensure that the money leaving an account matches the actual money spent. This is done by making sure the balances match at the end of a particular accounting period. — Jean Scheid, “Understanding Balance Sheet Account Reconciliation,” Bright Hub, 8 April 2011

Coming back to microservices, using the same principle we can reconcile data from multiple services on some action trigger. Actions could be triggered on a scheduled basis or by a monitoring system when failure is detected. The simplest approach is to run a record-by-record comparison. This process could be optimized by comparing aggregated values. In this case, one of the systems will be a source of truth for each record.

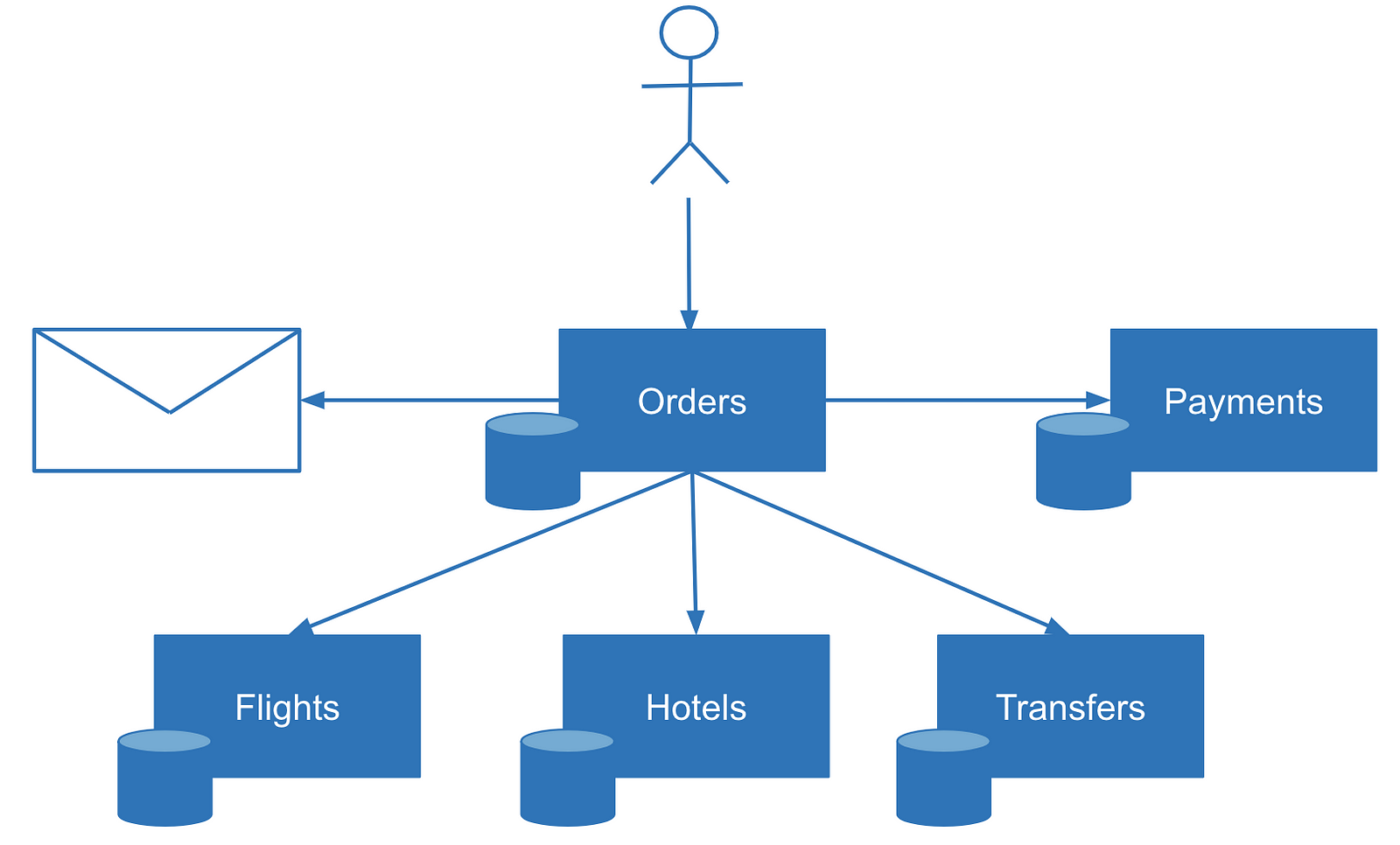

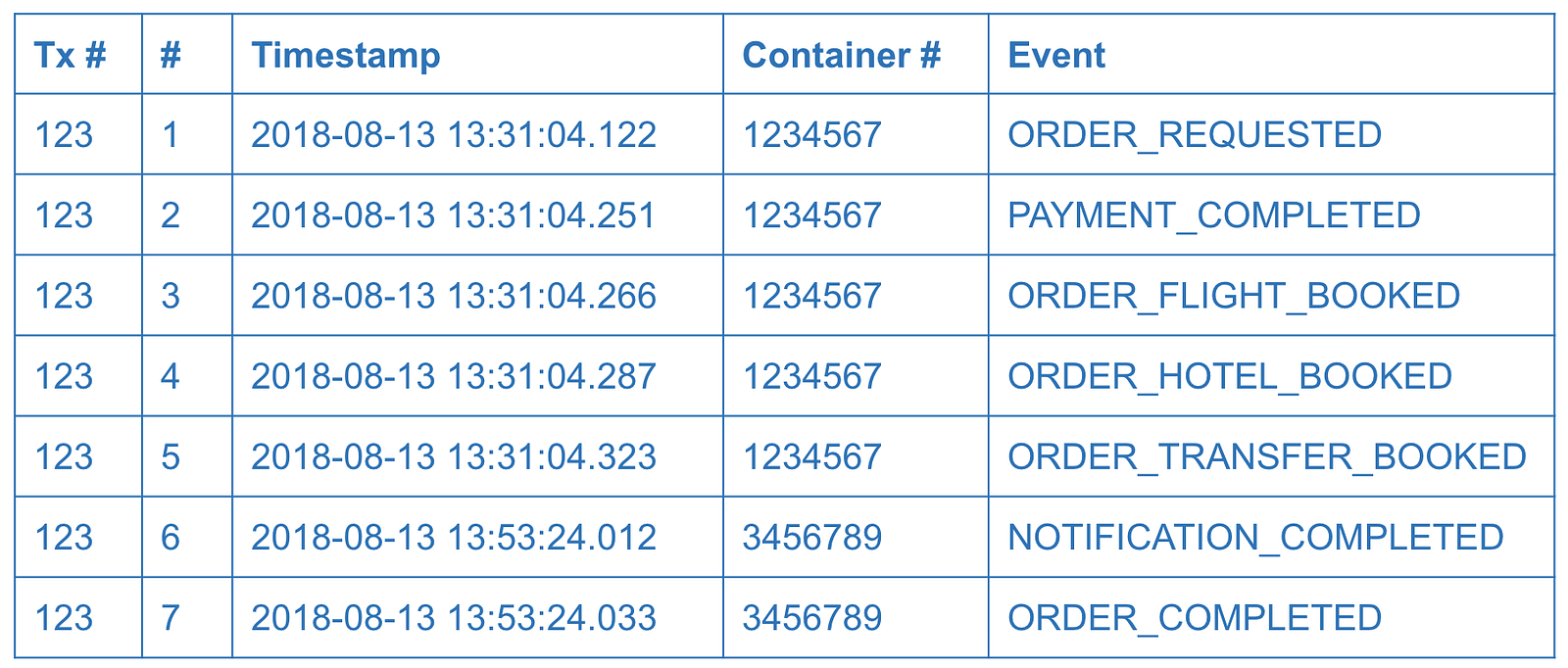

Event Log

Imagine multistep transactions. How to determine during reconciliation which transactions might have failed and which steps have failed? One solution is to check the status of each transaction. In some cases, this functionality is not available (imagine a stateless mail service that sends email or produces other kinds of messages). In some other cases, you might want to get immediate visibility on the transaction state, especially in complex scenarios with many steps. For example, a multistep order with booking flights, hotels, and transfers.

In these situations, an event log can help. Logging is a simple but powerful technique. Many distributed systems rely on logs. “Write-ahead logging” is how databases achieve transactional behavior or maintain consistency between replicas internally. The same technique could be applied to microservices design. Before making an actual data change, the service writes a log entry about its intent to make a change. In practice, the event log could be a table or a collection inside a database owned by the coordinating service.

The event log could be used not only to resume transaction processing but also to provide visibility to system users, customers, or to the support team. However, in simple scenarios a service log might be redundant and status endpoints or status fields be enough.

Orchestration vs. Choreography

By this point, you might think sagas are only a part of orchestration scenarios. But sagas can be used in choreography as well, where each microservice knows only a part of the process. Sagas include the knowledge on handling both positive and negative flows of distributed transaction. In choreography, each of the distributed transaction participants has this kind of knowledge.

Single-Write With Events

The consistency solutions described so far are not easy. They are indeed complex. But there is a simpler way: modifying a single datasource at a time. Instead of changing the state of the service and emitting the event in one process, we could separate those two steps.

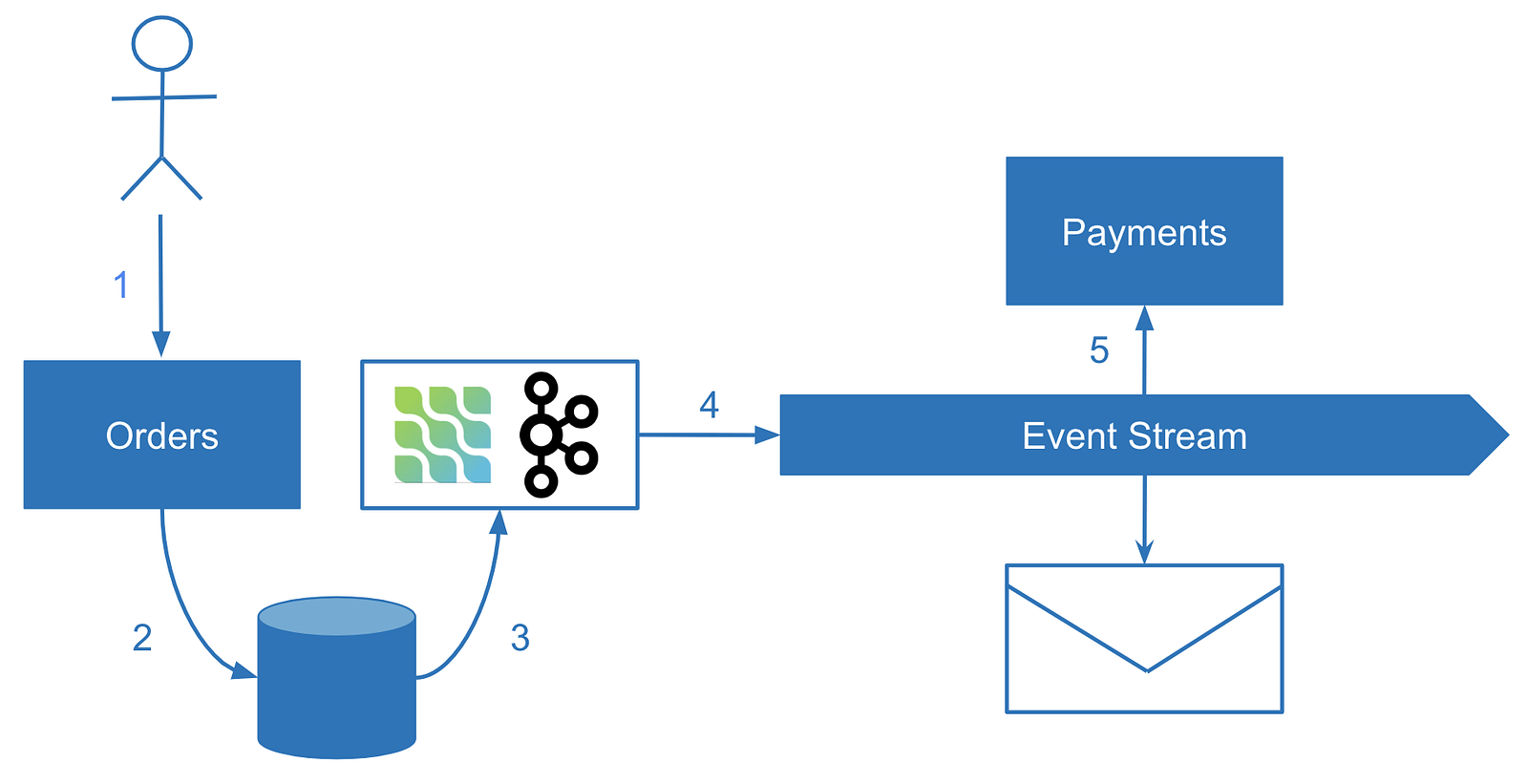

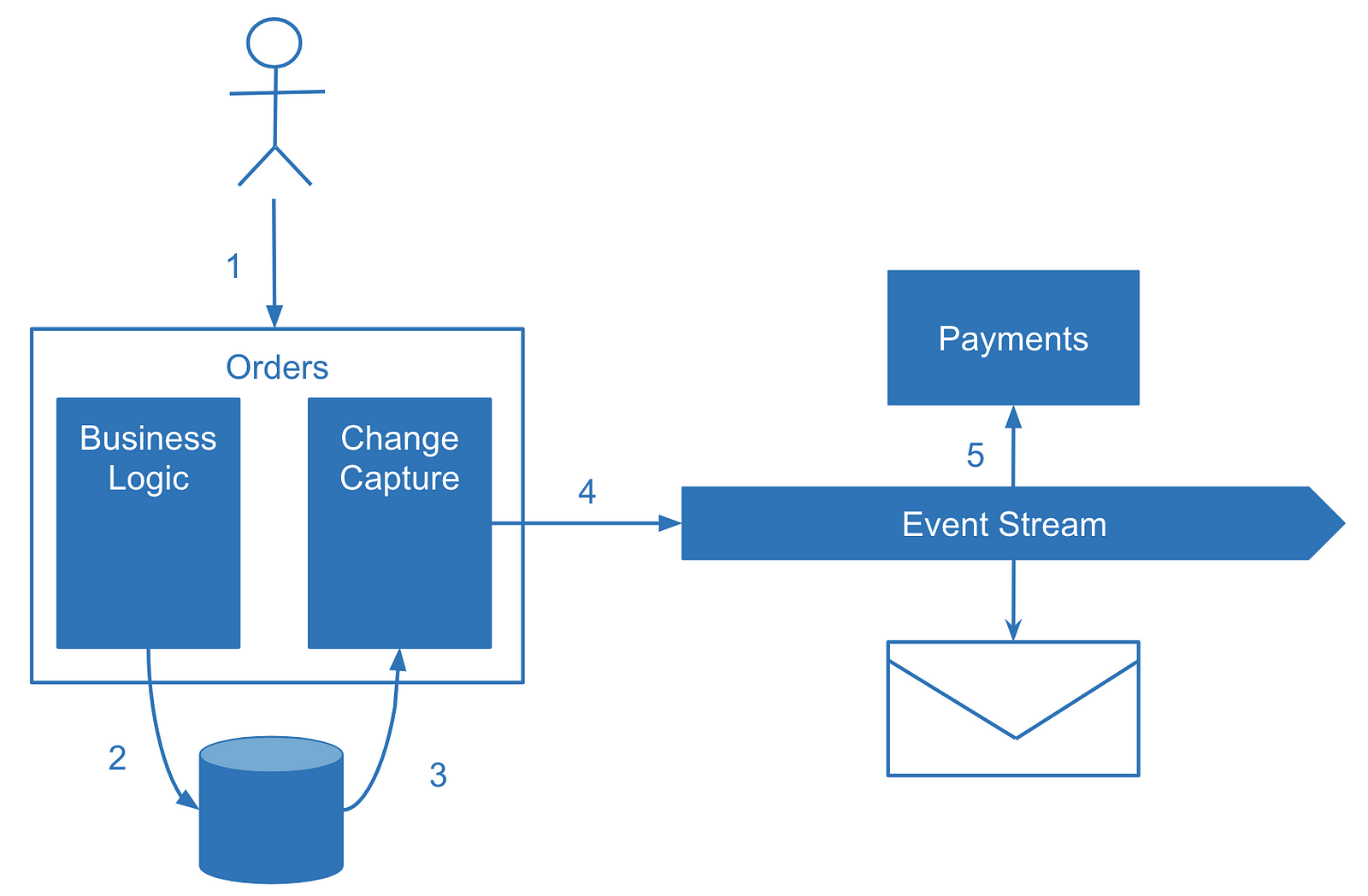

Change-First

In a main business operation, we modify our own state of the service while a separate process reliably captures the change and produces the event. This technique is known as Change Data Capture (CDC). Some of the technologies implementing this approach are Kafka Connect or Debezium.

However, sometimes no specific framework is required. Some databases offer a friendly way to tail their operations log, such as MongoDB Oplog. If there is no such functionality in the database, changes can be polled by timestamp or queried with the last processed ID for immutable records. The key to avoiding inconsistency is making the data change notification a separate process. The database record is, in this case, the single source of truth. A change is only captured if it happened in the first place.

The biggest drawback of change data capture is the separation of business logic. Change capture procedures will most likely live in your codebase separate from the change logic itself — which is inconvenient. The most well-known application of change data capture is domain-agnostic change replication such as sharing data with a data warehouse. For domain events, it’s better to employ a different mechanism such as sending events explicitly.

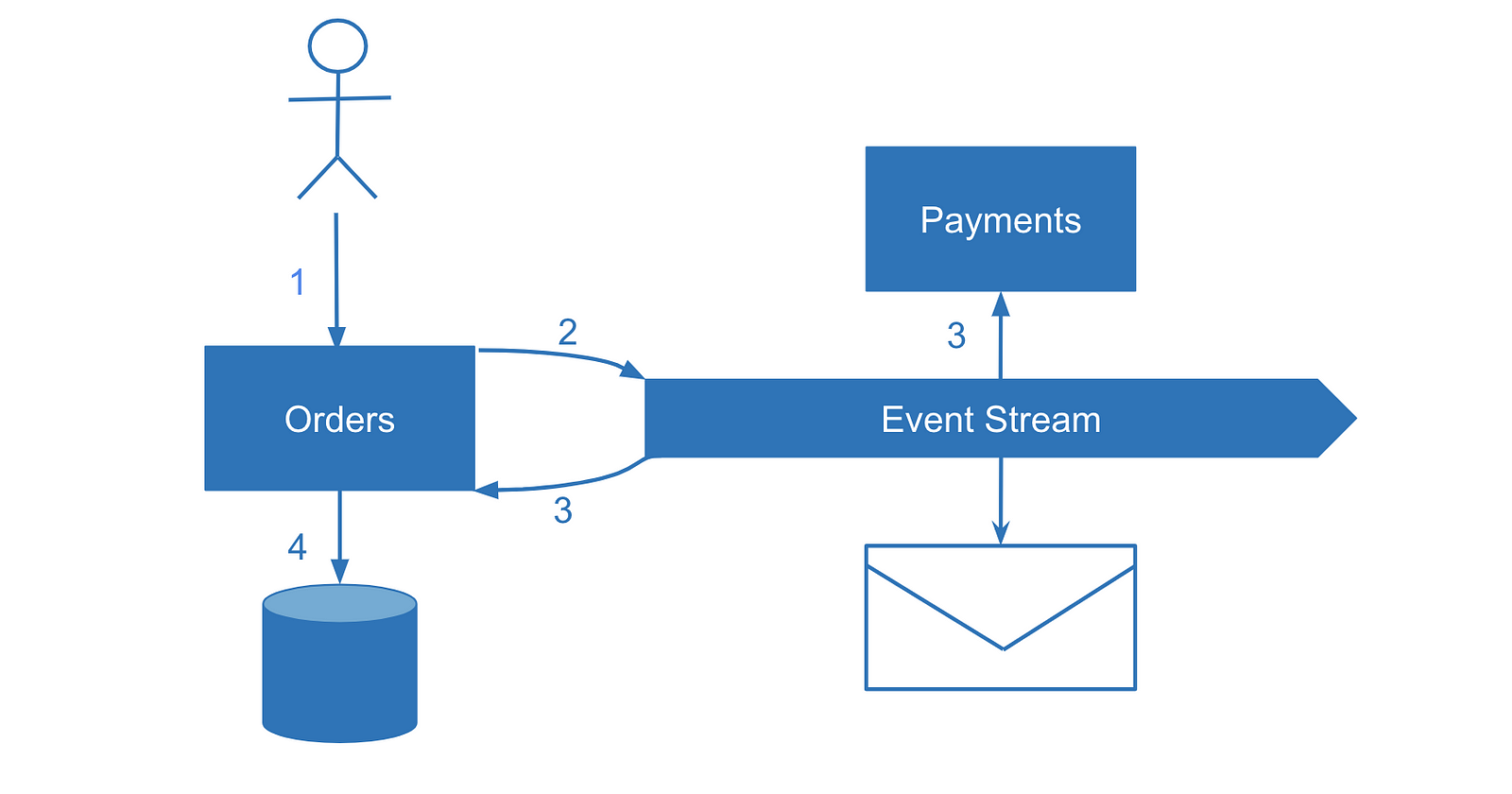

Event-First

Let’s look at the single source of truth upside down. What if instead of writing to the database first we trigger an event instead and share it with ourselves and with other services. In this case, the event becomes the single source of truth. This would be a form of event-sourcing where the state of our own service effectively becomes a read model and each event is a write model.

On the one hand, it’s a command query responsibility segregation (CQRS) pattern where we separate the read and write models, but CQRS by itself doesn’t focus on the most important part of the solution — consuming the events with multiple services.

In contrast, event-driven architectures focus on events consumed by multiple systems but don’t emphasize the fact that events are the only atomic pieces of data update. So I’d like to introduce “event-first” as a name to this approach: updating the internal state of the microservice by emitting a single event — both to our own service and any other interested microservices.

The challenges with an “event-first” approach are also the challenges of CQRS itself. Imagine that before making an order we want to check item availability. What if two instances concurrently receive an order of the same item? Both will concurrently check the inventory in a read model and emit an order event. Without some sort of covering scenario, we could run into troubles.

The usual way to handle these cases is optimistic concurrency: to place a read model version into the event and ignore it on the consumer side if the read model was already updated on the consumer side. The other solution would be using pessimistic concurrency control, such as creating a lock for an item while we check its availability.

The other challenge of the “event-first” approach is a challenge of any event-driven architecture — the order of events. Processing events in the wrong order by multiple concurrent consumers might give us another kind of consistency issue, for example processing an order of a customer who hasn’t been created yet.

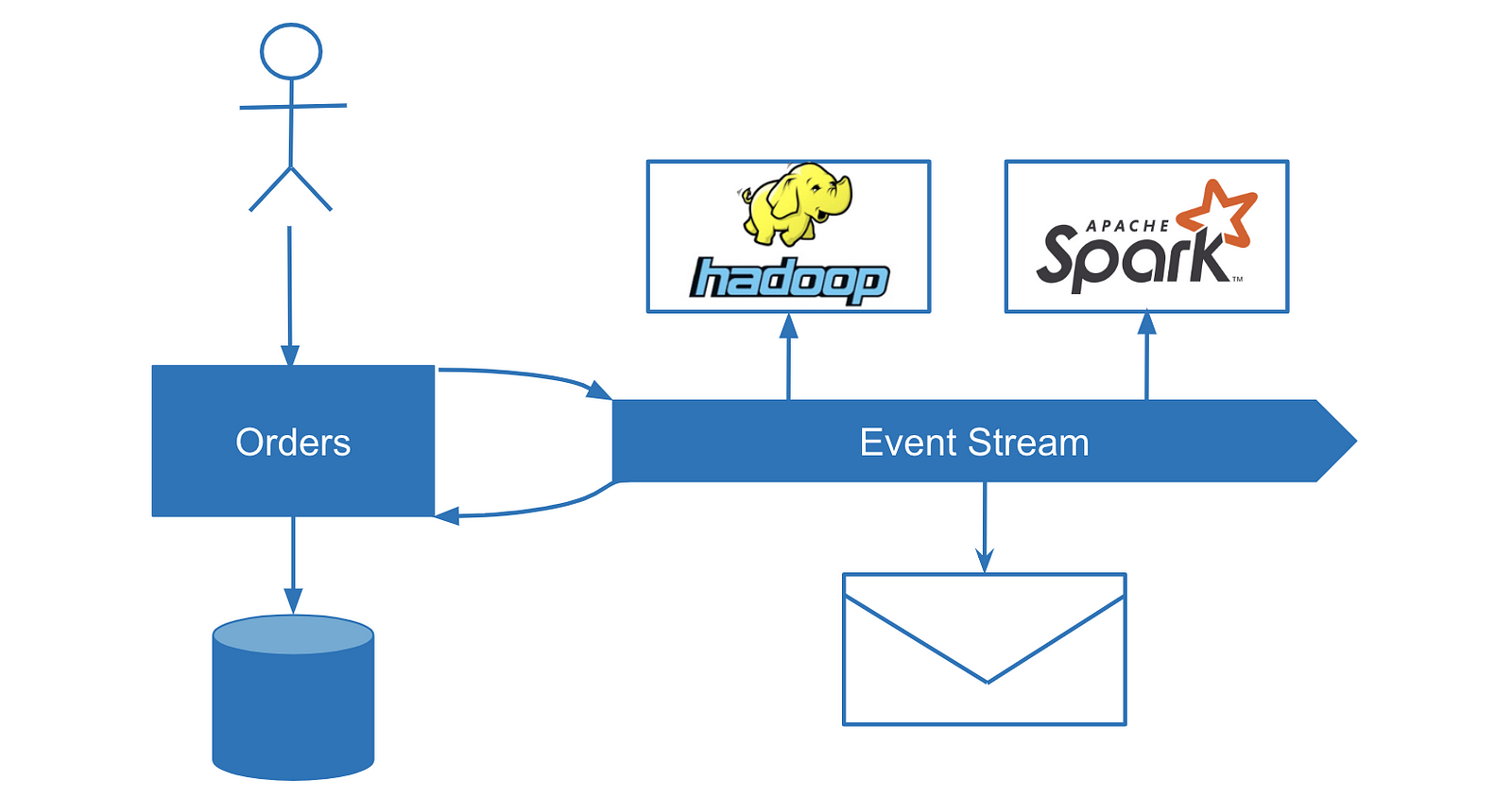

Data streaming solutions such as Kafka or AWS Kinesis can guarantee that events related to a single entity will be processed sequentially (such as creating an order for a customer only after the user is created). In Kafka for example, you can partition topics by user ID so that all events related to a single user will be processed by a single consumer assigned to the partition, thus allowing them to be processed sequentially. In contrast, in Message Brokers, message queues have an order but multiple concurrent consumers make message processing in a given order hard, if not impossible. In this case, you could run into concurrency issues.

In practice, an “event-first” approach is hard to implement in scenarios when linearizability is required or in scenarios with many data constraints such as uniqueness checks. But it really shines in other scenarios. However, due to its asynchronous nature, challenges with concurrency and race conditions still need to be addressed.

Consistency by Design

There many ways to split the system into multiple services. We strive to match separate microservices with separate domains. But how granular are the domains? Sometimes it’s hard to differentiate domains from subdomains or aggregation roots. There is no simple rule to define your microservices split.

Rather than focusing only on domain-driven design, I suggest to be pragmatic and consider all the implications of the design options. One of those implications is how well microservices isolation aligns with the transaction boundaries. A system where transactions only reside within microservices doesn’t require any of the solutions above. We should definitely consider the transaction boundaries while designing the system. In practice, it might be hard to design the whole system in this manner, but I think we should aim to minimize data consistency challenges.

Accepting Inconsistency

While it’s crucial to match the account balance, there are many use cases where consistency is much less important. Imagine gathering data for analytics or statistics purposes. Even if we lose 10% of data from the system randomly, most likely the business value from analytics won’t be affected.

Which Solution to Choose

Atomic update of data requires a consensus between two different systems, an agreement if a single value is 0 or 1. When it comes to microservices, it comes down to the problem of consistency between two participants and all practical solutions follow a single rule of thumb: In a given moment, for each data record, you need to find which data source is trusted by your system.

The source of truth could be events, the database or one of the services. Achieving consistency in microservice systems is the developers’ responsibility. My approach is the following:

- Try to design a system that doesn’t require distributed consistency. Unfortunately, that’s barely possible for complex systems.

- Try to reduce the number of inconsistencies by modifying one data source at a time.

- Consider event-driven architecture. A big strength of event-driven architecture in addition to loose coupling is a natural way of achieving data consistency by having events as a single source of truth or producing events as a result of change data capture.

- More complex scenarios might still require synchronous calls between services, failure handling, and compensations. Know that sometimes you may have to reconcile afterward.

- Design your service capabilities to be reversible, decide how you will handle failure scenarios and achieve consistency early in the design phase.

I will be sharing more thoughts on this topic at Voxxed Days Microservices in Paris. Join us!