What Are Microservices?

Microservices have been a major part of the software community since 2011, but as with many of the other architecture and design philosophies, there has been a punctuated hype surrounding this architecture style since its inception. As with many of these hypes, there has been a tendency to convert all existing software or mandate that all new software be implemented using this style. In response, many have dismissed this style as pure superficial hype, cynically expecting its prominence to be dethroned in much the same way as Service-Oriented Architectures (SOAs) and cross-platform object-oriented communication protocols (i.e. Common Object Request Broker Architecture, CORBA).

Somewhere between the hype and the cynicism, there are important advantages that microservices bring to the table, not only in terms of its reusability and modularity but also in terms of the software tools and technologies it facilitates in practice. In fact, this architecture style has been adopted by many of the largest enterprise application developers, including Amazon, Uber, Groupon, Capital One, Walmart, and Netflix (which alone accounted for 35.2% of all North American download internet traffic in 2016). With such monumental adoption, it benefits any serious software engineer and technologist to take heed of this practical approach.

In this article, we will explore the fundamentals of microservices, including a general definition that captures many of the characteristics of microservices, a brief history of how microservices came to be, and some of the tradeoffs that microservices present. Although microservices are a vast topic, both in terms of depth and breadth, we will focus on the overarching principles of the architecture, rather than on the specific implementation technologies. We will also explore some of the most popular and prolific resources that the interested reader can use to take the information from this overview and put it into practice.

A Simplified Definition

We usually look for a clean and crisp definition for different philosophies and architectures, but in the case of microservices, there does not exist one universally agreed upon definition. One reliable attempt was made by Microservices.io (created by Chris Richardson), which provides the following definition:

Microservices–also known as the microservice architecture–is an architectural style that structures an application as a collection of loosely coupled services, which implement business capabilities. The microservice architecture enables the continuous delivery/deployment of large, complex applications. It also enables an organization to evolve its technology stack.

James Lewis and Martin Fowler provide their own definition along the same lines:

The microservice architectural style is an approach to developing a single application as a suite of small services, each running in its own process and communicating with lightweight mechanisms, often an HTTP resource API. These services are built around business capabilities and independently deployable by fully automated deployment machinery. There is a bare minimum of centralized management of these services, which may be written in different programming languages and use different data storage technologies.

While both of these definitions may appear vague to some, they do well to capture the essence of a microservices architecture. In general, a microservices architecture involves the creation of individual services that perform a set business goal and are linked with minimalistic interconnections, such as Representational State Transfer (REST) Application Programming Interfaces (APIs). While the true definition of individual service may vary between applications, the general idea is that each service should solve one business goal and rely on other services to perform goals outside of its scope.

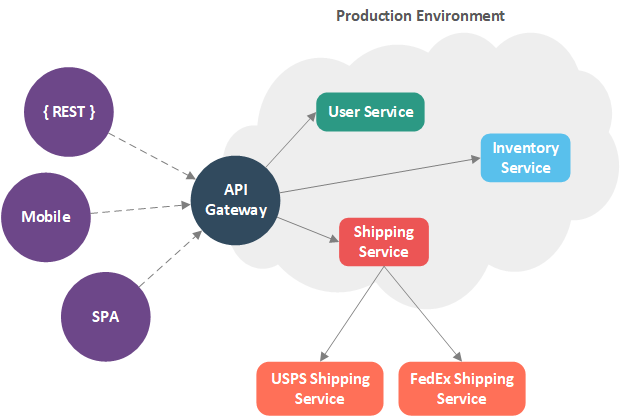

For example, suppose we wanted to create an online bookstore that allows registered users to submit orders, verify and update inventory, and ship books using the least expensive method (if the books are available). This application should be accessible using a mobile application, a client-side Single-Page Application (SPA) (run in a browser), and directly through a REST interface, with the mobile and SPA interfaces relying on the REST API. Using this description, we can divide our system into three main services, along with their respective responsibilities:

- User service: Manages the registered users

- Inventory service: Manages the stock of book currently available

- Shipping service: Handles finding the least expensive shipping service and shipping an order

Likewise, we can classify three main interfaces into our system:

- Mobile Application: Consumes the REST interface through an API Gateway/proxy

- Browser-based SPA: Consumes the REST interface through an API Gateway/proxy

- REST Interface: A Hypertext Markup Language (HTTP) REST interface that consumes and produces JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) resources; for our microservices implementation, each service will have its own REST interface and an API gateway will be used to compose these individual APIs into an apparently-singular REST API

Combining all of these divisions and interfaces into a single application, we can devise the following system diagram:

The Monolithic Way

If this were a simple system, we may combine each our services into a single application and create software interfaces to facilitate interactions between the services. In turn, we would create a single REST interface that allows for requests to be handled by each of the services. Likewise, we would utilize a shared data store. In essence, we would create a nominal three-tier application, with a REST interface on top, the domain and business logic (for users, inventory, and shipping combined) in the middle, and a data layer (which interacts with our shared data store and each of the external shipping services) at the bottom.

The Microservices Way

In a more realistically scaled application, we can benefit greatly by dividing each of the services into their own applications, with their own process space. For example, we can create a separate user service that has its own data store, own business and domain logic, and own REST interface. Likewise, we can repeat the same process for the inventory and shipping services. This results in independent and highly cohesive services, as illustrated in the system diagram above.

This division allows us to create well-encapsulated miniature (or micro) services that do one thing very well. Since each has its own process space, we can deploy them independently, as well. This allows us to make changes to a single microservice without affecting the others. This also allows us to scale portions of the system that become overloaded. For example, if we were to create a single application, we would be forced to deploy new instances of the entire applications behind a load-balancer to share the workload. If only the shipping service is overloaded, we are forced to create new instances of the user and inventory services as well, but these new instances will likely go unused (or else share a load that a single instance could have handled without the overhead of load-balancing).

In the microservices approach, we can scale the part of the application (the shipping service in this case) that requires more resources. In essence, microservices provide us a higher level of granularity in deployment, but this fineness comes with some disadvantages. Primary among them is the need for more nuanced orchestration. For example, had we combined our system into a single application, we would have shared a process space and calls between services would be as trivial as making a method call to another object in memory. With microservices, we are now responsible for ensuring that messages between services are mapped correctly, allowing each of the services to communicate with each other through their respective REST APIs.

While orchestration may be a concern for microservices, the interconnections between services should be as simple as is feasible and constitute just enough capability to facilitate minimal communication between services. Unlike the days of SOAs with Enterprise Service Buses (ESBs), the smarts in the microservices architecture are contained within the services, rather than within the connections between the services.

The Idealistic Microservice Environment

The flexibility of deployment and scaling not only allows us to make more fine-grained decisions about how an application is deployed at runtime, but it also allows us to introduce a high-degree of automation into our production system. For example, theoretically, we can create a delivery pipeline for each of our services, creating relationships between the pipelines that reflect the dependency relationships between the services. When a change is made to the codebase for a service, the delivery pipeline for that service is started. As the pipeline for the altered service is executed, all dependent pipelines are subsequently executed.

Once the service has been built and tested (its pipeline stages have all passed), the service, along with its dependencies (whose pipelines have also passed all stages) are packaged into containers and deployed to the production environment. This idealistic environment is illustrated in the figure below.

On top of the deployment environment depicted above, a similar setup can be established for spinning up new instances of microservices to automatically scale to meet the needs of the production environment. For example, once the pipeline for a service is finished, the service is containerized and stored in a repository. If more instances of the service are needed, such as during high-stress or large-traffic times of the day, more instances of the containerized microservice can be deployed automatically to meet these immediate needs. When the immediate need for more service instances subsided, the containers can be removed and the resource usage of the system returns to its normal levels.

While the combination of delivery pipeline technologies is a great goal, containerized technologies, and the microservices philosophy, the nuances of real-world applications make this ideal system difficult to implement. For example, suppose that an application consisted of twenty microservices, all with dozens of their own dependencies and required interfaces. As the size of the system grows, orchestrating a large number of microservices can become prohibitively difficult.

In pragmatic applications, complete automation (from the point of developers checking in code to an updated microservice being deployed and scaled in a production environment) may not be possible, but even partial implementations of these concepts can greatly reduce the fragility of a production system.

A Simplified Definition Revisited

With an understanding of the thought process behind microservices and some of the advantages they present, we can create a simplified definition for a microservices architecture:

A microservices architecture is one in which the business goals of a system are divided into independent, encapsulated, and decoupled services that interact with each other through well-defined remote interfaces

While this definition may lack some of the details and specificity of other definitions, it provides a baseline for understanding microservices. The restriction of independence and encapsulation results in defensively programmed services that are able to cope with the failure, upgrade, or scaling with minimal impact. In practice, the well-defined remote interface of the microservices will be some type of web-based technology, such as WebSockets, Protocol Buffers, or HTTP REST interfaces, although any technology that can communicate between process spaces will suffice.

In order to obtain a deeper understanding of microservices, we must explore how microservices came to be, specifically what technologies and philosophies the microservices architecture supplanted as it grew and matured.

The Evolution of Enterprise Applications

Modularity and componentization have long been a part of software engineering, but microservices have been a relatively recent concept that stems from a long and storied history of architectures. While many of the underlying concepts have been around since the infant days of software engineering, the idea of creating a networked array of miniature, special-purpose services had its start at the most basic of all architectures: The monolithic architecture.

Monolithic Architecture

A monolith is a single, massive stone structure and since the dawn of software development, most systems have had an uncanny resemblance to these edifices. In most software, we simply bind together all of our code into a single, gigantic project, with all of the business logic, interfaces, frameworks, and data stores into a single application. While this may sound like a poor way to structure an application, it is very effective for a wide range of use cases.

For example, the user, inventory, and shipping microservices can be thought of as monoliths. Viewed in the big picture of the bookstore application, they are simple microservices, but if we focus on just one of these services, they are a singular, three-tier application with a user interface (REST API), business logic, and data store.

While monoliths suffice for small-scale applications or small services, it is wholly inadequate for the massive scale of the applications that are developed and deployed today. For applications like Netflix, which processes more than 400 billion events every day, such an oversimplified architecture is deficient in both its development and deployment. In the early days of the internet era, a new type of architecture was conceived to solve this conundrum: SOA.

Service-Oriented Architecture

Unlike a monolithic architecture, SOA is much more standardized architecture, almost to a fault. Instead of having a single application handle all types of services in a system, an SOA delineates each of the major portions of a system into services with very precise interfaces. More than just a collection of services, SOA also includes a large centerpiece: The ESB.

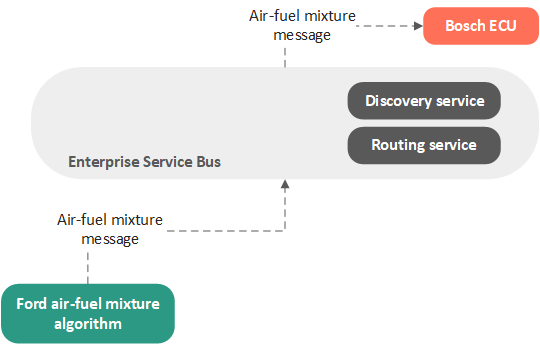

The goal behind many SOA implementations is to create a standardized set of services (which consume and produce data) and attach them to a singular ESB. The ESB is then responsible for pairing up producers and consumers and allowing services to discover one another. It should be noted that the interface for each service, or class of services, is highly standardized, and is likely contractual.

For example, we can create an SOA for a car by creating a centralized ESB that allow for different devices (services) to be attached. We can then add contracts for desired devices, such as an Engine Control Unit (ECU). In order to attach an ECU to the ESB, we implement a service that fully conforms to the contractual interface for an ECU and registers with the ESB. When other services on the bus wish to make changes to the engine (such as changing the air-fuel mixture), they send a message to the ESB. The ESB then recognizes that our ECU service is capable of performing this action and routes the message to our ECU service. This scheme is illustrated in the figure below.

It is important to note that the service that sent the air-fuel mixture update message not know anything about our ECU service and may not have even known that our ECU service was registered on the bus. Instead, it simply produced a message and instructed the ESB to find a consumer for the message. The ESB, which knew of our ECU service and recognized that it was a consumer of air-fuel mixture update messages (this was discovered when it registered as an implementation of the ECU interface contract), forwarded the message to the ECU. It is important to note that most of the message routing and decision making takes place in the ESB: In general, the smarts of the application are contained within the ESB.

In theory, this approach would allow completely orthogonal service implementations to attach to the same bus and interoperate. For example, we could create an ESB implementation within a Ford vehicle that allowed for a Ford algorithm to send air-fuel mixture update messages to the bus and have a Bosch ECU perform the necessary changes to the engine. The beauty of this architecture is that the Ford algorithm has no concept of the Bosch ECU, only that there is a subscriber for the air-fuel mixture messages that it produces.

While this idea was theoretically sound, it required a prohibitively stringent set of contract interfaces and a very complex ESB to be created. In practice, this meant numerous and complex Web-Service Descriptor Language (WSDL) contracts for online applications and countless proprietary interface contracts for localized applications. While some SOA implementations were fruitful, on the whole, millions of dollars were spent to create SOA ESBs to little avail. What was needed was a compromise between monoliths and ESBs: Small services with simple communication interfaces.

Microservices Are Different

The microservices architecture is similar to SAO but has some major differences. Like SOA, the microservice architecture is composed of encapsulated services, but the interface contracts are much more relaxed. Instead of proprietary or complicated contract descriptors, microservices use minimalistic interfaces that utilize REST over HTTP with predefined JSON (or other information transfer formats, such as eXtensible Markup Language, XML) request and response bodies. This not only removes the need for strict contracts, it also removes the need for the ESB.

With microservices architectures, the smarts of the architecture are in the leaves rather than the branches: Services contain the business logic and make requests directly to other services (or through a proxy or a gateway) rather than using centralized routing or discovery. In essence, microservices are the equilibrium between the pendulum swings of monolithic architectures and SOA.

Advantages & Disadvantages

Just like any other philosophy or approach in software engineering, microservices are intended to solve problems within a specific context. As such, microservices have their fair share of advantages and disadvantages.

Advantages

Some of the major advantages of using a microservices architecture include:

- Services are relatively small and self-contained (small relative to the size of an equivalent monolithic application).

- A change to one service does not necessarily elicit a change in other services.

- Services can be deployed and scaled independently of other services, or even deployed in separate containers using a container technology, such as Docker; build and delivery pipelines can be used to automate deployment, with a change to a service causing an automated build, test, and deployment of the service, along with the other services that depend on it.

- Services can be developed independently, with possibly different languages and technology stacks, different developers, or even with different organizations.

- Portions of the system can be hot-swapped without bringing down the entire application

- A failure in one service in the system does not necessarily halt the entire application (the boundaries between portions of the system are more defined and each portion is more isolated in a microservice architecture than with a monolithic application).

- Testing services in isolation is easier.

Disadvantages

While microservices are effective for some applications, they also carry some disadvantages, including:

- Services may contain duplicated logic or development effort may be duplicated between multiple services.

- Greater orchestration is required.

- Testing the entirety of the system is more difficult due to the need for network routes and other communication pathways between services.

- Dividing services cleanly can be difficult (or, as SoapUI Pro phrases it: "Partitioning the application into microservices is very much an art").

- Properly encapsulating transactions between services can be difficult; for example, do we create an order ID in the inventory service and have each item added to the order as separate messages (using the order ID) or do we wait for a message containing a complete list of items in an order to be sent to the inventory service?

- More resources, such as memory, may be required when microservices are deployed (compared to an equivalent monolithic application).

- Connections between services are often times more complex that monoliths (not in terms of the complexity of individual connections, such as with SOA, but in terms of the number of connections between the various microservices).

More Information

Although we have not gone into the details of creating a microservice at the code level, or how to migrate an existing application to a microservice architecture, there are many valuable resources available on these topics. While the following list is not exhaustive, it contains some of the most recognized and cited books and articles on microservices and will help in understanding microservices at a practical level:

- Microservices by James Lewis & Martin Fowler: James Lewis and Martin Fowler's take on microservices. Although many new microservices technologies and frameworks have appeared since it was published in early 2014, this article still captures the main characteristics of the microservice architecture. It is an excellent resource for both new and experienced microservices developers and vividly summarizes the guiding principles of microservices without pigeonholing its overview with specific technologies and open-source projects.

- Building Microservices by Sam Newman: The de-facto book on microservices which contains useful guidance on the principles of microservices. This book does not purport to teach its reader how to implement microservices in detail (as that depends on the individual application and problem domain at hand), but rather, sheds some light on the techniques used by microservices designers and architects to create practical solutions in production environments.

- Microservices Guide by Martin Fowler: A compendium for any microservices designer. This single page contains a vast array of microservices information, including great quotes, lectures, presentations, interviews, and a host of other assorted learning materials.

- Getting Started with Microservices by Vineet Reynolds & Arun Gupta: The official DZone Refcard on microservices. This Refcard is great for any developer or architect looking to gain a quick, concise overview of the world of microservices (including migration of monoliths into microservices and the common patterns of microservices) without becoming inundated with details.

- The Netflix TechBlog: The official technical blog for the Netflix software engineering community. Being that Netflix is one of the major post-children for microservices on a large scale, the Netflix TechBlog has numerous articles written by Netflix engineers who primarily share their first-hand experiences with implementing microservices for arguably the largest enterprise application ever developed.

- Microservices.io: A digest created by Chris Richardson that includes catalogs of microservices patterns, articles and presentations on microservices, and other learning resources to get developers off the ground.