Event-Driven Microservices?

When Vikas Anand, Product Director of Google’s Apigee API Management offering, gave the presentation "The Case for a Unified API and Event Strategy" during the recent EDA Summit of 2022, I was again shocked by a gleaming error in what was presented: “Microservices, while they’re providing a great deal of advantages, they also bring in complexity which you need to manage. We can basically manage this better by providing a solution which is called event-driven architecture. This produces a solution for this problem, of microservices and a solution at scale, where it provides the ability to reduce dependencies and complexities in your application, whilst still allowing the creation of more and more microservices.”

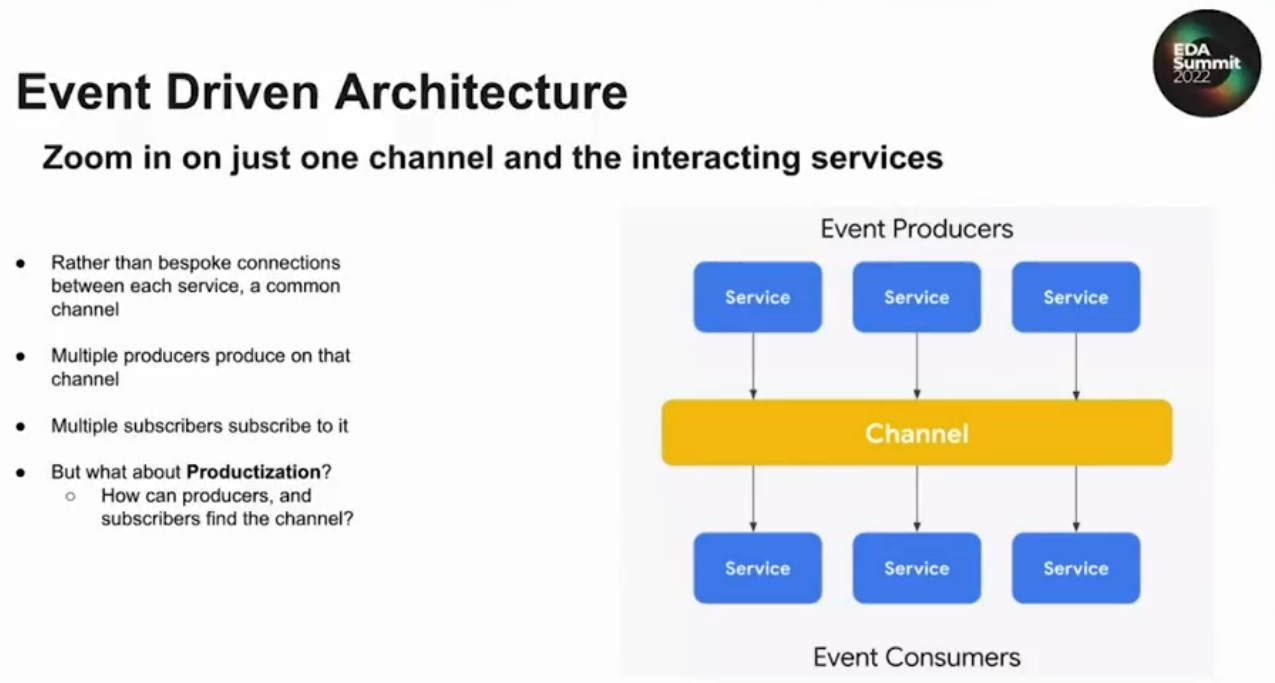

Although I genuinely have no idea what any of that means, an error was nonetheless evident in the associated slide:

Here, Vikas apparently decided to simply forget that microservices are always deployed as "competing consumers," in constant competition with each other for workload. Yet, if we look carefully at Vikas’ vanilla-EDA slide, this essential detail is nowhere to be seen and is in no way supported. We are instead shown a single "event channel" and told, “Multiple subscribers subscribe to it," meaning multiple microservices. This is apparently why he claims that an EDA approach is “allowing the creation of more and more microservices.”

What is not explained is why each of the three microservices shown in this diagram – each of the three "competing consumers" – would not all perform exactly the same task when they each receive exactly the same event from exactly the same channel to which they are all subscribed. Indeed, any event would quite obviously lead to the same task being performed 3 times in the above example, which is completely devoid of any notion of competing consumers.

Despite this, Vikas informs us that “event-driven microservices” are nevertheless the future: “This produces a solution for this problem of microservices and a solution at scale, where it provides the ability to reduce dependencies and complexities in your application.” It would seem that Vikas suggests reducing “complexities in your application” by simply ignoring those complexities. Should we instead think seriously about these complexities, what we ought to understand is that microservices cannot be "event-driven" using today's techniques – only ever "event-oriented" (e.g., by using a message broker along with its target-specific message queues, rather than an event broker and its openly accessible topics). This is precisely why I suggested in mid-2020 that the EDA community should instead take ownership of a new concept: macroservices.

Macroservices– unlike today's microservices– can be "event-driven," as they do not represent "competing consumers." Instead, their workload is managed by a single "software component" with a single database that will launch individual macroservices operations just as soon as it has an available "work process" (which ought to be most of the time, if the server is correctly sized). Such a macroservice approach is analogous to the ultra-performant Node.js event loop, an approach towards which a great many developers are shifting today. This is an approach that demands a tiny fraction of the complexity and cost of a microservices landscape, perhaps the reason for which Uber publicly started abandoning microservices in April 2020 (see Tweets by @GergelyOrosz).

There is in fact a second gleaming error in Vikas’ brave new world of “event-driven microservices.” Precisely because of the competing consumer constraint, microservice endpoints are triggered synchronously today. Events, on the other hand, are always delivered asynchronously: the broker has to first determine if there are any subscribers to a topic before being able to actually deliver any new events – in no particular order – to ALL topic subscribers.

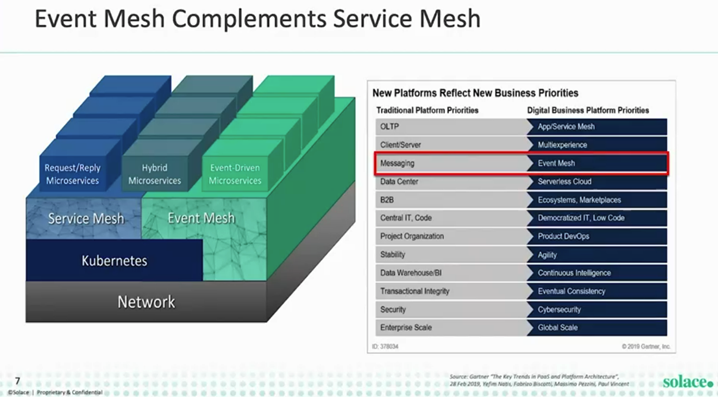

To avoid giving the impression of Google-bashing – despite the enormity of the discussed omissions – I prefer to mention that we see exactly the same error in a presentation by the CTO of the EDA Summit sponsor, Solace. Shawn McAllister told us during his presentation "Powering Your Real-Time, Event-Driven Enterprise with PubSub+ Platform" that the retail sector is also moving towards “event-driven microservices,” and provides us with the following slide where, once again, we are given the impression that “event-driven microservices” work side-by-side in perfect harmony and cooperation, while at the same time being entirely independent of one another. Competing microservices, we are again asked to believe, simply need to subscribe to the same topic(s) on the "event mesh", and each of these autonomous event consumers will somehow be aware of which events have, or have not already been treated – asynchronously – by their competing consumer peers.

Rather than merely pointing out to both Google and Solace that their “event-driven microservices” presentations simply do not compute, it is in fact relatively easy to provide them with a little help: Microservices – competing consumers – cannot possibly subscribe to the same channel/topic for their workload. Instead, each requires its own dedicated topic, exactly as per the dedicated message queues of a message broker, but with a major twist: there needs to be a dedicated topic to which each microservice publishes its availability – something which appears to have no equivalent today in the world of message brokers (which typically distribute the workload on a sub-optimal, round-robin basis). Once any possible worker – "microservice" or otherwise – comes online, it simply needs to publish its availability to the workload dispatcher(s). As new work appears, the workload dispatcher(s) – just like the Node.js event loop – simply needs to consume the events published to the "worker availability" topic in sequential order, publishing any new workload to the dedicated worker topic that was nominated in the latest Worker.Available event.

While I have little doubt that a nearly identical approach has been used by operating system developers for decades (given that any kernel obviously needs to be made aware of the fresh availability of work processes), what might be considered revolutionary with such a broker-centric approach is that those workers publishing their availability to the "worker availability" topic need no longer be running upon the same hardware, unlike the work processes of old. Indeed, it is very easy to imagine your domestic workload being shared between your under-utilized PC, laptop, mobile phone, television, and fridge CPUs in parallel: each working in perfect harmony, at their own pace.