Acceptance Tests in Java With JGiven

Most of the developer community knows what a unit test is, even if they don’t write them. There is still hope. The situation is changing. More and more projects hosted on GitHub contain unit tests.

In a standard setup for Java projects like NetBeans, Maven, and JUnit, it is not that difficult to produce your first test code. Besides, this approach is used in Test Driven Development (TDD) and exists in other technologies like Behavioral Driven Development (BDD), also known as acceptance tests, which is what we will focus on in this article.

Difference Between Unit and Acceptance Tests

The easiest way to become familiar with this topic is to look at a simple comparison between unit and acceptance tests. In this context, unit tests are very low level. They execute a function and compare the output with an expected result. Some people think differently about it, but in our example, the only one responsible for a unit test is the developer

Keep in mind that the test code is placed in the project and always gets executed when the build is running. This provides quick feedback as to whether or not something went wrong. As long the test doesn’t cover too many aspects, we are able to identify the problem quickly and provide a solution. The design principle of those tests follows the AAA paradigm. Define a precondition (Arrange), execute the invariant (Act), and check the postconditions (Assume). We will come back to this approach a little later.

When we check the test coverage with tools like JaCoCo and cover more than 85 percent of our code with test cases, we can expect good quality. During the increasing test coverage, we specify our test cases more precisely and are able to identify some optimizations. This can be removing or inverting conditions because during the tests we find out, it is almost impossible to reach those sections. Of course, the topic is a bit more complicated, but those details could be discussed in another article.

Acceptance tests are classified the same as unit tests. They belong to the family of regression tests. This means we want to observe if the changes we made to the code have no effects on already worked functionality. In other words, we want to secure that nothing that is already working got broken because of some side effects of our changes. The tool of our choice is JGiven. Before we look at some examples, first, we need to touch on a bit of theory.

JGiven In-Depth

The test case we define in JGiven is called a scenario. A scenario is a collection of four classes: the scenario itself, the Given displayed as "given (Arrange)," the Action displayed as "when (Act)," and Outcome displayed as "then (Assume)."

In most projects, especially when there are a huge amount of scenarios and the execution consumes a lot of time, acceptance tests get organized in a separate project. With a build job on your CI server, you can execute those tests once a day to get fast feedback and to react early if something is broken. The code example we use to demonstrate contains everything in one project on GitHub because it is just a small library and a separation would just over-engineer the project. Usually, the one responsible for acceptance tests is the test center, not the developer.

The sample project TP-CORE is organized by a layered architecture. For our example, we picked out the functionality for sending e-mails. The basic functionality to compose an e-mail is realized in the application layer and has a test coverage of up to 90 percent. The functionality to send the e-mail is defined in the service layer.

In our architecture, we decided that the service layer is our center of attention in defining acceptance tests. Here, we want to see if our requirement to send an e-mail is working well. Supporting this layer with our own unit tests is not that efficient because, in commercial projects, it just produces costs without winning benefits. Also, having also unit tests means we have to do double the work because our JGiven tests already demonstrate and prove that our function is well working. For those reasons, it makes no sense to generate test coverage for the test scenarios of the acceptance test.

Let’s start with a practice example. At first, we need to include our acceptance test framework into our Maven build. In case you prefer Gradle, you can use the same GAV parameters to define the dependencies in your build script.

Listing 1

<dependency>

<groupId>com.tngtech.jgiven</groupId>

<artifactId>jgiven-junit</artifactId>

<version>0.18.2</version>

<scope>test</scope>

</dependency>As you can see in listing 1, JGiven works well together with JUnit. An integration to TestNG also exists: you just need to replace the artifactId for jgiven-testng. To enable the HTML reports, you need to configure the Maven plugin in the build lifecycle, like it is shown in Listing 2.

Listing 2

<build>

<plugins>

<plugin>

<groupId>com.tngtech.jgiven</groupId>

<artifactId>jgiven-maven-plugin</artifactId>

<version>0.18.2</version>

<executions>

<execution>

<goals>

<goal>report</goal>

</goals>

</execution>

</executions>

<configuration>

<format>html</format>

</configuration>

</plugin>

</plugins>

</build>

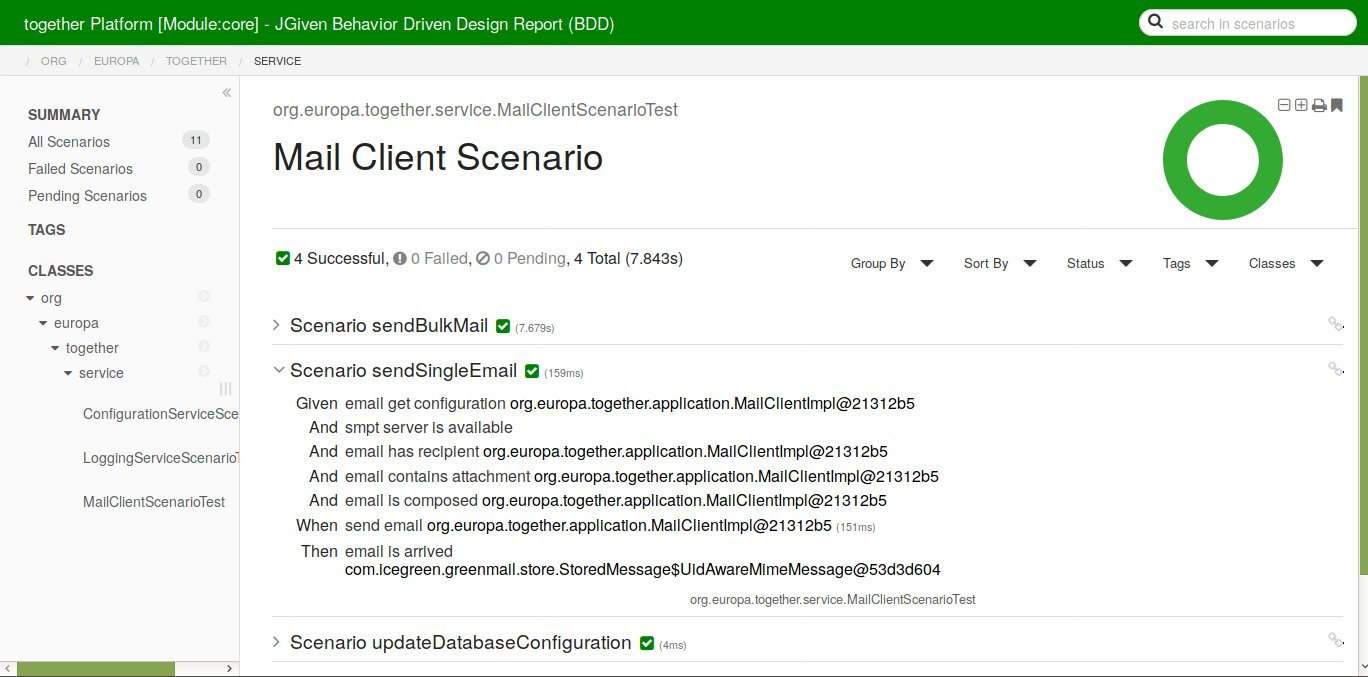

The report of our scenarios in the TP-CORE project is shown in the image above. As we can see, the output is very descriptive and human-readable. This result will be explained by following some naming conventions for our methods and classes, which will be explained in detail below. First, let's discuss what we can see in our test scenario. We defined five preconditions:

- The configuration for the SMPT server is readable.

- The SMTP server is available.

- The mail has a recipient.

- The mail has attachments.

- The mail is fully composed.

Producing Descriptive Scenarios

Now is a good time to dive deeper into the implementation details of our send e-mail test scenario. Our object under test is the class MailClientService. The corresponding test class is MailClientScenarioTest, defined in the test packages. The scenario class definition is shown in listing 3.

Listing 3

@RunWith(JUnitPlatform.class)

public class MailClientScenarioTest

extends ScenarioTest<MailServiceGiven, MailServiceAction, MailServiceOutcome> {

// do something

}As we can see, we execute the test framework with JUnit5. In the ScenarioTest, we can see the three classes: Given, Action, and Outcome in a special naming convention. It is also possible to reuse already defined classes, but be careful with such practices. This can cost some side effects. Before we now implement the test method, we need to define the execution steps. The procedure for the three classes is equivalent.

Listing 4

@RunWith(JUnitPlatform.class)

public class MailServiceGiven

extends Stage<MailServiceGiven> {

public MailServiceGiven email_has_recipient(MailClient client) {

try {

assertEquals(1, client.getRecipentList().size());

} catch (Exception ex) {

System.err.println(ex.getMessage);

}

return self();

}

}

@RunWith(JUnitPlatform.class)

public class MailServiceAction

extends Stage<MailServiceAction> {

public MailServiceAction send_email(MailClient client) {

MailClientService service = new MailClientService();

try {

assertEquals(1, client.getRecipentList().size());

service.sendEmail(client);

} catch (Exception ex) {

System.err.println(ex.getMessage);

}

return self();

}

}

@RunWith(JUnitPlatform.class)

public class MailServiceOutcome

extends Stage<MailServiceOutcome> {

public MailServiceOutcome email_is_arrived(MimeMessage msg) {

try {

Address adr = msg.getAllRecipients()[0];

assertEquals("JGiven Test E-Mail", msg.getSubject());

assertEquals("noreply@sample.org", msg.getSender().toString());

assertEquals("otto@sample.org", adr.toString());

assertNotNull(msg.getSize());

} catch (Exception ex) {

System.err.println(ex.getMessage);

}

return self();

}

In case you ask yourself where the assert methods come from, the answer is very easy. This is the integration of the JUnit5 test framework we are using. That means if an assertion fails, the whole scenario fails too.

Now, we see how the names of the methods correspond with the output of the report. This demonstrates to us the importance of well-chosen names to keep the context understandable. After we defined the steps to pass the scenario, we have to combine them in the scenario test class. Let's demonstrate how we can demonstrate this in listing 5 where we extend the implementation of listing 3 with the scenario_sendSingleEmail() function.

Listing 5

private MailClient client = null;

public MailClientScenarioTest() {

client = new MailClientImpl();

//COMPOSE MAIL

client.loadConfigurationFromProperties("org/europa/together/properties/mail-test.properties");

client.setSubject("JGiven Test E-Mail");

client.setContent(StringUtils.generateLoremIpsum(0));

client.addAttachment("Attachment.pdf");

}

@Test void scenario_sendSingleEmail() {

client.clearRecipents();

client.addRecipent("otto@sample.org");

try {

// PreCondition

given().email_get_configuration(client)

.and().smpt_server_is_available()

.and().email_has_recipient(client)

.and().email_contains_attachment(client)

.and().email_is_composed(client);

// Invariant

when().send_email(client);

//PostCondition

then().email_is_arrived(SMTP_SERVER.getReceivedMessages()[0]);

} catch (Exception ex) {

System.err.println(ex.getMessage);

}

}Now, we completed the cycle and we can see how the test steps got stuck together. JGiven supports a bigger vocabulary to fit more necessities. To explore the full possibilities, please consult the documentation.

Lessons Learned

In this short workshop, we passed all the important details to start with automated acceptance tests. Besides JGiven other frameworks exist fighting for usage, like Concordion or FitNesse. Our choice for JGiven was its helpful documentation, simple integration into Maven builds and JUnit tests, and descriptive human-readable reports.

A negative point, which could people keep away from JGiven, could be the detail that you need to describe the tests in the Java programming language. That means the test engineer needs to be able to develop in Java if they want to use JGiven. Besides this small detail, our experience with JGiven is absolutely positive.

Further Reading

- Automating REST Acceptance Tests

- Kill Your Dependencies: Java/Maven Edition