Layered Architecture Is Good

Darek, the guy who reviews almost all Tidy Java posts before they are published, suggested that I could do a series on implementing different architectural styles — their pros, cons, etc. I decided to give it a try, and here comes the first one – Layered Architecture. To avoid misunderstandings, let me note that I will present the Layered Architecture as I was taught/learned, which might be different than the one you know or some sources present. Enjoy!

What Is Layered Architecture?

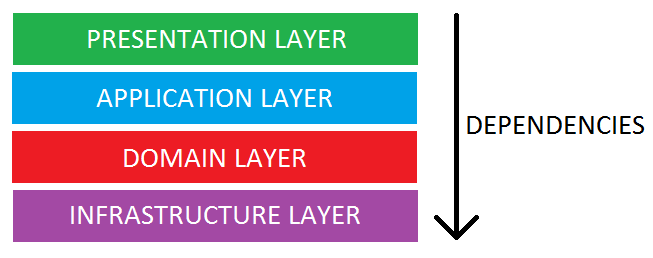

A Layered Architecture, as I understand it, is the organization of the project structure into four main categories: presentation, application, domain, and infrastructure. Each of the layers contains objects related to the particular concern it represents.

- The presentation layer contains all of the classes responsible for presenting the UI to the end-user or sending the response back to the client (in case we’re operating deep in the back-end).

- The application layer contains all the logic that is required by the application to meet its functional requirements and, at the same time, is not a part of the domain rules. In most systems that I've worked with, the application layer consisted of services orchestrating the domain objects to fulfill a use case scenario.

- The domain layer represents the underlying domain, mostly consisting of domain entities and, in some cases, services. Business rules, like invariants and algorithms, should all stay in this layer.

- The infrastructure layer (also known as the persistence layer) contains all the classes responsible for doing the technical stuff, like persisting the data in the database, like DAOs, repositories, or whatever else you’re using.

There are two important rules for a classical Layered Architecture to be correctly implemented:

- All the dependencies go in one direction, from presentation to infrastructure. (Well, handling persistence and domain are a bit tricky because the infrastructure layer often saves domain objects directly, so it actually knows about the classes in the domain)

- No logic related to one layer’s concern should be placed in another layer. For instance, no domain logic or database queries should be done in the UI.

The Essence of Layered Architecture

Architecture is kind of an overloaded term, so we should probably dig deeper into what the term really means in the context of layers. The main idea behind Layered Architecture is a separation of concerns – as we said already, we want to avoid mixing domain or database code with the UI stuff, etc. The actual idea of separating a project into layers suggests that this separation of concerns should be achieved by source code organization. This means that apart from some guidance to what concerns we should separate, the Layered Architecture tells us nothing else about the design and implementation of the project. This implies that we should complement it with some other architectural processes, such as some upfront design, daily design sessions, or even full-blown Domain-Driven Design. Whichever option we choose doesn’t matter, at least for the sake of layering, but we need to remember: Layered Architecture gives us nothing apart from a guideline on how to organize the source code.

Implementing Layered Architecture

Equipped with the knowledge of the layers to create, the relationships between them and the essence of the architecture, we are ready to implement it. As most of you probably expect, we will slice the system into layers by creating a separate package for each of them. When it comes to applying the dependency and separation rules, things are not so obvious. One could try putting each layer in a separate Maven module, but then capturing the weird relationship between domain and persistence would not be easy. I usually stick with packages and use common sense along with code reviews to make sure that none of the rules are broken.

Layering Spring Pet Clinic

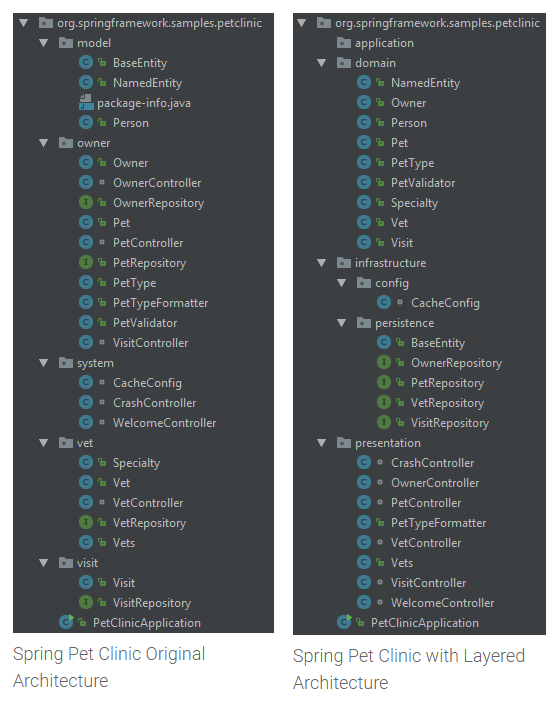

Since I didn’t want to force you to learn a new project just to grasp a simple idea, I decided to use a project that all Java developers should be familiar with – Spring Pet Clinic. At the time of writing this post, the project uses some weird packaging, that is probably supposed to be more domain-oriented. Let’s see how the two ways of code organization stack against each other:

I’ll leave the interpretation to you. One thing that I did not expect, which is now clear, is that there were no application services in the project – almost everything is done in the controllers! I haven’t seen it until I actually moved the classes to their best-fit layer packages.

Benefits of a Layered Architecture

Although some of you might still not believe it, Layered Architecture has some benefits, including:

- Simplicity – the concept is very easy to learn and visible in the project at first grasp.

- Consistent across different projects – the layers and so the overall code organization is pretty much the same in every layered project.

- Guaranteed separation of concerns – just the concerns that have a layer and to the point that you stick to the rules of Layered Architecture, but it’s very easy with the code organization it implies.

- Browsability from a technical perspective – when you want to change something in some/all objects of a given kind, they’re very easy to find and they’re kept all together.

Drawbacks of a Layered Architecture

And, of course, Layered Architecture is not perfect. Some of its cons include:

- No built-in scalability – when the project grows too much, you need to find a key to organizing it further by yourself. The principles of Layered Architecture won’t help you.

- Hidden use cases – you can’t really say what a project is doing by simply looking at the code organization. You need to at least read the class names and, unfortunately, sometimes even the implementation.

- Low cohesion – classes that contribute to common scenarios and business concepts are far from each other because the project is organized around separating technical concerns.

- No dependency inversion – in a classical Layered Architecture, the dependencies are direct and, conceptually, changes from a low-level infrastructure layer can propagate to more important higher layers.

When to Apply Layered Architecture

At first, I wanted to write some cases when I use Layered Architecture myself, but I think we could use a more methodical approach based on its pros and cons:

- Simplicity: That’s obviously important for everyone. The non-existent learning curve makes it especially viable for low-experience teams and the ease of applying for projects with no budget to invest in a more advanced architecture.

- Consistency: Multiple small projects handled by the same group of people, such as an internal architecture for microservices.

- Separation of concerns: Low-experience teams.

- Technical browsability: To some extent, it helps everyone. It depends on what you’re trying to find at a given moment.

- No built-in scalability: Projects that are supposed to stay small, such as microservices, or larger projects that can be easily factored into smaller pieces.

- Hidden use cases and low cohesion: Projects with no or few complex business scenarios, such as CRUD operations or simple REST services.

- No dependency inversion: Projects with few dependencies on the infrastructure, in which there are no serious low-level changes to actually propagate higher.

Summary

As you can see, a Layered Architecture has its bright and dark sides. To me, its simplicity and consistency make it a good fit for microservices without too much serious business logic. One could question if such microservices should exist in the first place, but the realities of factoring big monoliths often make them a lesser evil. The most important lesson that you should take away from this article is: Layered Architecture is about organizing code for a good separation of concerns and nothing else, really.