Microservices and Team Organization

This article is featured in the new DZone Guide to Microservices. Get your free copy for more insightful articles, industry statistics, and more!

Microservices architectures are unique because they can be extremely flexible over time and impact a project’s organization at any time. This can be very challenging for companies, as it can force them to question their organizational model, which may not have necessarily moved much in most companies. Perhaps the first good question to ask yourself when you start using this kind of architecture is: “what is your organization capable of?” In my opinion, this is a prerequisite to know what difficulties will be encountered and to start arming yourself in the early stages.

But let’s first come back to the link between architectures and microservices. When it comes to organizing teams and microservices, the famous Conway law is often mentioned. This law, which is becoming more and more widely accepted, has not always been approved of in the past. The main flaw in the attainment of the absolute truth of this law is that it is more a sociological law than a purely scientific law.Indeed, it has always been demonstrated in an empirical way, based on examples and not on pure scientific logic. It is difficult to demonstrate sociological results in general, because these demonstrations are largely based on intangible considerations and on concepts, and can only be verified by multiplying the examples to infinity.

But let us get to the facts and quote this law: “Organizations which design systems... are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structure of these organizations.”

From this law, we can draw some simple reflections:

If I want a specific architecture, I need an organization aligned with my architecture.

On the other hand, if I have to change my architecture often, I have to be able to modify my organization just as often.

These two assertions, which echo the principle of inverse Conway maneuver, have far-reaching consequences. They underpin an organization’s ability to adapt, which would ignore careerist tendencies, resistance to change, ultraspecialization of skills, and so on. They can also lead to philosophical reflections on the primacy of the machine over the human, but I am already digressing.

The corollary of all this is that the first question to be asked when we want to make a microservices architecture is: “How adaptable is the organization to this type of architecture?”Of course, it’s tempting to think about Netflix and Amazon, but is your company ready? It is important to take this into account in order to quickly detect the brakes and “tricks” to circumvent the constraints.

One of the tricks to quickly ramp up is feature teams. Feature teams bring together several different skills to create a feature. But this can quickly become insufficient, because as your architecture explodes into microservices, coordination needs will arise.

One other trick is the open source governance model. Open source projects, because of their decentralized structure, make it possible to create highly decoupled software, which is what we want in microservices architectures. It may therefore be advisable to work in this way with other teams, with a small team having the code, and one or more extended teams being able to push changes in the code.

But what about the acceptance of this logic and organizational changes in a company? Are these tricks sufficient to instill coordination, skills, and knowledge throughout your company? Decentralized organizations build decoupled code, but technical or functional skills and knowledge shouldn’t be decoupled to the extreme, either. It’s like if you rob Peter to pay Paul, but here you rob shared knowledge to build decoupled architectures.

The real stalemate is more cultural than anything else, and a number of management styles that have emerged in recent years can help unblock the situation.

A fairly good example of what can be done to go further is the Spotify framework (although we should limit ourselves to metaframeworks, because it is mostly a state of mind). Spotify uses the concepts of feature teams and governance with an opensource approach, but complements these tools with a matrix model of agility at scale. Matrix organizations have the magic to ensure that you always get to know someone who knows the person who has the knowledge or skill.

So, when I studied the organizations of teams using microservices, I thought that something was missing.New management methods have become popular recently and could have an interesting influence, especially in organizations seeking to implement microservices.

Indeed, we touched on the subject of corporate culture, organization, and resistance to change. The first type of management that comes directly to my mind is holacracy.

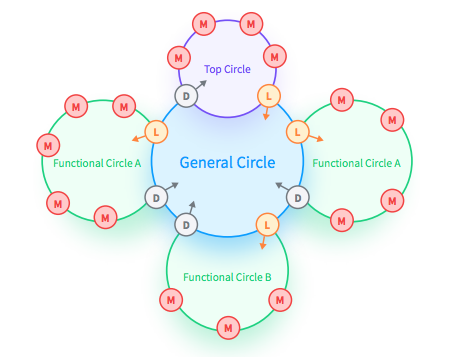

Holacracy is a fractal organization divided into autonomous and independent entities that are themselves linked to higher entities. These same entities are represented in the form of circles that can overlap with each other, and which have the particularity of being self-organizing while being managed by the upper circle. Each circle is thus very responsive to change in its nature and composition. The gains observed by this type of management are the involvement, cooperation, and simplicity of the links between people.

We could imagine, for example, that the elementary circles would be the microservices development teams, that the upper circles would be made up of architects and product owners, and that the top circle would be the client business lines of your application. This would give rise to product owners and architects who could coordinate the business needs, while ensuring that the best practices instigated by architects are implemented.

I say “we could imagine” because it is up to you to decide your needs and your solutions according to the desired architecture.One of the driving forces behind this circle organization is Domain-Driven Design, often used in microservices projects. Indeed, this way of building applications typically brings developers, software architects, and experts in the field around the same table. All can potentially come from different circles or overlapped circles. It is therefore interesting to set up this type of organization in order to improve the transmission of knowledge and the time it takes to set up the architecture.

Contrary to what we might think, this type of management is relatively compatible with a traditional hierarchical organization. Indeed, even if the hierarchy is flattened, it still persists, and it can be circumscribed to IT project teams, in case your CxOs see this with bad eyes.

In case a holacracy cannot take hold in your organization, you can seek inspiration from sociacracy (also called Dynamic Governance). Sociacracy is not a mode of organization like holacracy, but more of a mode of governance without a centralized power structure, also operating under the principle of circles. These circles may also have overlapping boundaries and are made up of the group's constituent elements, as well as delegates from the group and a group leader. Unlike holacracy, sociacracy aims to manage fewer operational subjects to focus on problems or strategic questions. It is thus a mode of governance that can perfectly be superimposed on any organization and can be an intermediate step to a more disruptive organization such as a holacracy.

As we can see, other management styles exist, and can provide solutions to the extremely changing nature of microservices architectures. I am convinced that studying the impact of these architectures will lead companies to rethink their organizational models, to the delight of employees and customers alike. There is still the question of support for change and corporate culture. My opinion is that the corporate culture must always be respected but also reformed because it will ultimately be the driving force behind the evolution of your organizations.

This article is featured in the new DZone Guide to Microservices. Get your free copy for more insightful articles, industry statistics, and more!